FATHER HESBURGH OF NOTRE DAME:

ATTEMPTING TO MAKE A GREAT CATHOLIC

UNIVERSITY

WHILE RIDING THE TIGER

by James M. Thunder*

*The author is a Washington,

D.C., attorney. He double-majored in theology and government at Notre Dame. He

has written articles online severely critical of the Catholic nature of Notre

Dame’s current president.

We shall always hope to find

them [newly-free

countries] strongly supporting their own

freedom--and to remember that, in the past, those who foolishly sought power by

riding the back of the tiger ended up inside.

President John F. Kennedy’s

Inaugural Address, 1961

Fr. Hesburgh rode

the back of the tiger. Did he end up inside? Father Wilson D. (“Bill”) Miscamble

has authored the 400-page biography, American

Priest: The Ambitious Life and Conflicted Legacy of Notre Dame’s Father Ted Fr.

Hesburgh (Image) that answers this question in the affirmative.

Fr. Hesburgh, born

in 1917 a few days apart from John F. Kennedy, had the same ambition – to

aspire to be the best, and to be accepted by the American public and

establishment. Both men had achieved this goal by 1960. Sixty years on, we

wonder whether we who are Catholic, Evangelical, Orthodox Jew, or Mormon, all

of us who “cling to our religion” (Obama 2008), can long thrive amidst the

hostility of the media, academia, and the Democratic Party.

Fr. Hesburgh’s

35-year tenure as president of Notre Dame (1952-1987) and a life of 97 years

(1917-2015), makes researching a biography daunting. The book covers the entire

97 years. The “essential basis” of the book are 30 hours of Fr. Miscamble’s interviews

of the subject in June 1998, 11 years after he had left office and eight years

after he had written his autobiography God,

County, Notre Dame. Fr. Hesburgh knew at the time that Fr. Miscamble had an

abiding interest in the Catholic mission of the university. Fr. Miscamble had

come to Notre Dame from Australia in 1976 for a doctorate in history, had

entered Fr. Hesburgh’s religious Order (Holy Cross/CSC) in 1982, and had joined

the history faculty at Notre Dame in 1988. He was chair of the History

Department when he obtained Fr. Hesburgh’s consent in 1994 to a biography that

would offer a critical evaluation of his life, by which point Fr. Hesburgh knew

Fr. Miscamble had participated in a faculty Conversation

on the Catholic Character of Notre Dame in 1992 and 1993. (In 2013, Fr.

Miscamble assembled his essays, beginning in 1993, in For Notre Dame: Battling for the Heart & Soul of a Catholic

University). His critical evaluation is not like the accolades Fr.

Hesburgh received upon his retirement or upon his death or in the current

100-minute documentary film Fr. Hesburgh.

Without a doubt, Fr. Hesburgh achieved acceptance by the public and establishment

in America. For example, he was appointed by nine presidents 16 times between

1954 and 2001. LBJ awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom (1964) and the

Congress its Gold Medal (2000). He was on the cover of TIME (1962), served on the board of the Rockefeller Foundation

(1961-82; chair 1977-82), was Chair, Overseas Development Council

(1971–82), a

director of Chase Manhattan Bank (1972-82), on the

Board of Overseers, Harvard University (1990-96; chair 1994-96); and on the board of the Association of American

Colleges and Universities (president in 1961).

In the

second half of the book, Fr. Miscamble, in a smooth writing style, puts these

various roles off campus in historical context with the people and events and

he assesses Fr. Hesburgh’s effectiveness. (I mean his effectiveness on the work

at hand. Fr. Hesburgh was always effective in networking to the benefit of his

reputation and that of the university.) I count 20 activities evaluated by Fr.

Miscamble covering the 42 years from 1954 (National Science Board) to 1996

(Chair, Board of Overseers, Harvard). Of

these, I count 13 he evaluated extremely positively.

The first half of the

book focuses on Fr. Hesburgh’s role as president of Notre Dame. Fr. Hesburgh had been appointed

president at age 35 to a single six-year term. His five immediate predecessors

(back to 1922) had served single six-year terms. Church (canon) law imposed this

term limit for religious superiors and, until 1958, Notre Dame presidents

served simultaneously as religious superiors. Why did Fr. Hesburgh fail to

groom a successor for 1958 (as he himself had been groomed for three years as

Executive Vice President), or for 1982 when he turned 65? Why did he turn down

being head of NASA (1968), heading the poverty program (1969), or running for

Vice President with McGovern (1972)? Just because he thought these roles

inappropriate for a priest? Hardly, he was willing to be on the Rockefeller

Foundation and Chase Manhattan Bank boards. No. No matter what else he did, he

wanted to remain head of Notre Dame, to continue working to make Notre Dame a

great, indeed, the great, Catholic

university.

When Fr. Hesburgh

surveyed the landscape in 1952, he found no great Catholic universities

anywhere in the world. There had been great Catholic universities, but he would

not try to imitate or replicate the medieval universities. As he said in an

April, 1961, speech: “I have no ambitions to be a medieval man.” To make Notre

Dame the great Catholic university became his life’s work and it did not matter

that his ambition was for a university of only 5,000 students, in obscure northern

Indiana, operated by a religious Order founded just 115 years earlier (not, for

example, by the Jesuits with their 400-year history in education), known as a

third-rate school with a first-rate football team (Frank Leahy had won four

national championships from 1943-49), in the context where Americans, like

Father John Tracy Ellis, had described Catholic college education as mediocre,

and in an America in which the WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant)

establishment had long discriminated in education (and jobs, etc.) against

Catholics, Italians, Irish, Poles, Germans, Hispanics.

Since there were

no models for great Catholic universities in the 20th century, what

specifically did Fr. Hesburgh want? It may be easier to describe what Fr.

Hesburgh was against than what he was for. He was against interference by the

Vatican, interference by the Holy Cross Order, interference by his bishop in

particular or the American bishops in general.

Fr. Hesburgh had a

visceral reaction to interference by the Italian-dominated Eurocentric Vatican.

He didn’t want any Catholic university to be, as he said in his 1998 interviews

with Fr. Miscamble, “under the thumb of some monsignor in Rome who wouldn’t

know a university from a cemetery…” When Fr. Miscamble describes Fr. Hesburgh

as an “American priest,” he means not only a patriot, but also one who would

compare favorably with American Jesuit Father John Courtney Murray (1904-1967)

whose views about “the American experiment with democracy” were adopted by the

Vatican II document on religious liberty.

Fr. Hesburgh

oversaw the development of two highly important documents that asserted

freedom, independence, from the Church: the 1967 “Land o’ Lakes Statement” issued

by a small group of Catholic university leaders; and the 1972 “The Catholic

University in the Modern World” issued by the International Federation of

Catholic Universities (of which he was chair, 1963-70).

He also did not

want to be under the thumb of his own Holy Cross Order. So 1967 was important

for this additional reason. That year he completed an agreement that

transferred ownership and control of most of the campus to a lay board (while requiring

that the president be a Holy Cross priest and requiring that the “Fellows”

guarantee the university’s Catholic identity in perpetuity).

Looking at the

1952 baseline, let’s postulate that Notre Dame in 1952 was Catholic and see if,

as it obtained secular acceptance and grew (ranked 23th in endowment

in 1987), it became more, or less, Catholic. Catholic by what criteria? Let’s

put aside the “superficial,” a word used by Fr. Hesburgh in a Chicago Tribune interview upon assuming

office and would well describe the headcount-at-Mass metric used by a

predecessor of Fr. Hesburgh. “Our emphasis on religion isn’t something

that is tacked on to the program, but a fiber running through our entire

educational structure. We want religion to be important, but we do not want it

in a sentimental or superficial way.” (David Condon, ND ’45, reprinted in “President Hesburgh,” Notre Dame, Vol. 5, No. 3, Fall 1952, pp. 3-5.)

What about the school’s curriculum? There would have been nothing in 1952

contrary to the Catholic Church’s official teaching (“magisterium”) as part of

the formal instruction. There’d have been nothing Protestant. Thomas Aquinas

(Thomism) was front and center. As for pedagogical tools, Fr. Hesburgh was

against rote learning. Furthermore, Fr. Hesburgh wanted the curriculum to be an

“ordered assembly,” not a “crazy quilt,” of course offerings.

Although 10% of the students in

1952 were not Catholic, one could conceive of a great Catholic university with

no Catholic students; it would be a purely missionary endeavor. (Think of

Chicago parochial schools in the 2000s.) In the 1952 interview, Fr. Hesburgh

pointed out that its alumni association president and its former board chair

were not Catholics.

What about faculty as a criterion

of Catholicity? (For greatness, he wanted faculty to have doctorates, from

leading institutions. He wanted “excellence.” Fr. Miscamble says the word was

part of his “mantra.” He despised mediocrity, incompetence. It was not enough

for Holy Cross faculty to have just the academic training needed for

ordination.) In 1952, there were 500 faculty, 80 of whom were priests and 80

non-Catholics. “Father Cavanaugh Reports on His Stewardship,” in “[NYC] Dinner

of the President’s Committee,” Notre Dame Alumnus, vol. 30, no. 1,

Jan-Feb 1952, pp.5-6, http://www.archives.nd.edu/alumnus/vol_0030/vol_0030_issue_0001.pdf.. We can safely say that all of the Catholic and non-Catholic

faculty were supportive of Notre Dame’s Catholic mission.

Fr. Hesburgh lost his way. He ended

up inside the tiger. According to Fr. Miscamble, he didn’t pay attention to

“who teaches” and “what is being taught.” When Fr. Hesburgh toured Europe in

1954, he did so to recruit Catholic faculty.

When Fr. Hesburgh retired in 1987, only two-thirds of the 950 faculty members

were at least nominally Catholic, but the people doing the hiring were not

seeking Catholics, much less devout Catholics, for the faculty: “[T]rends were

well set in place…that led to what Philip Gleason [Notre Dame professor of

history] described [in a 2001 article] as ‘a hollowing-out of the Catholic

character of the faculty, in umbers, self-identification, and group morale.’”

In 1952, a

large percentage of the Catholic students would have received a Catholic

education before arriving on campus in Catholic grade school and/or high

school. That changed greatly during Fr. Hesburgh’s tenure as increasing numbers

attended public grade schools and high schools. In 1987 (and today) anyone,

whether members of the public, students, parents, or donors, might think that a

Catholic education would include the Bible, the Church’s social teaching (war

and peace, racial justice, labor, migration), Catholic bioethics (abortion,

euthanasia), Catholic sexuality (marriage, contraception), a history of the

Church and of charity, readings of the “Fathers of the Church” and the “Doctors

of the Church,” in sum, exposure to the rich Catholic intellectual tradition. No

Notre Dame graduate in 1987 was, or is today, required to have such a

grounding. It is possible today to receive such a grounding at Notre Dame, but

in 2015, almost

immediately after the alumni organization Sycamore Trust in collaboration with

Fr. Miscamble posted his description of

faculty and courses that would provide such a grounding, http://www.ndcatholic.com/, the organization reported

that Father had been forbidden (presumably by a religious superior) from

maintaining any ties to the project.

As with the

large secular (private and state) universities, Notre Dame saw, and is

continuing to see, the proliferation of courses and majors and minors and

compartmentalized, independent, departments. At the same time this incoherent,

non-integrated approach to education was happening at Notre Dame, Fr. Hesburgh

was ironically establishing multidisciplinary institutes, including the Environmental Research Center (late

‘60s), Center for Civil and Human

Rights) (1973), Kellogg Institute for International Studies (1978), Kroc

Institute for International Peace Studies (1985). (The Medieval Institute (1946)

and Program of Liberal Studies (1950) pre-dated Fr. Hesburgh’s presidency.) And

off campus he established the multidisciplinary Tantur Ecumenical Institute for

Theology Studies, Jerusalem (1972).

These

institutes reflected Fr. Hesburgh’s particular passions but they also evidenced

his belief that a great Catholic university should be involved in the great

issues of the day. He wanted the university to be involved without being

partisan. There is no evidence that he perceived abortion as a great issue of

the day – about which he or the university should be involved. Fr. Miscamble

traces the arc. For example, after the January 1973 decision of Roe v. Wade, Fr. Hesburgh remained

silent until he gave a major address at Yale in December. When he raised it, he

was hissed.

In 1998,

Fr. James T. Burtchaell, who had been chair of Theology (1968-70) and Provost (and assumed successor) (1970-77), published the

first The Dying of the

Light: The Disengagement of Colleges and Universities from Their Christian

Churches in which examined

17 American colleges. Although Notre Dame was not among them, Fr. Hesburgh knew

that the book implicitly criticized the secularization of Notre Dame under Fr.

Hesburgh. Fr. Miscamble allows that Fr. Hesburgh often did not recognize the

consequences of his decisions. One such decision was selecting Timothy O’Meara

as provost (1978-1996), although a Catholic, he had no training in the

humanities (he was a mathematician) and no particular concern for Catholic education.

|

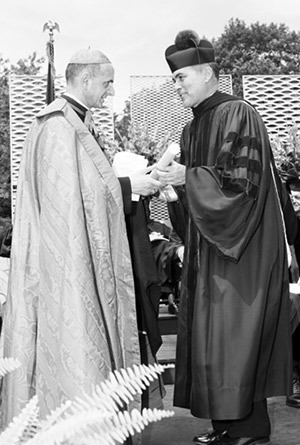

| President, Fr., Hesburgh with Cardinal Montini at Notre Dame’s 1960 commencement. |

I’d like to end with two notes of sadness. What might have been for Notre Dame’s Catholicity if Fr. Hesburgh had had better relations with two popes? Fr. Hesburgh met Cardinal Montini (later Paul VI) on campus in 1960 and they became fast friends, including watching movies on space exploration at the Vatican. Fr. Hesburgh responded to Paul VI’s idea regarding an ecumenical center and got it, the Tantur Center I just mentioned, built. But Fr. Miscamble describes their 1969 rupture. When Paul VI reached out to re-establish their relationship, Fr. Hesburgh snubbed him. In an interview on World Over Live on March 13, Fr. Miscamble said Fr. Hesburgh visited Paul VI’s tomb whenever he was in Rome in order to fulfill an early promise he had made to Paul VI to visit him whenever Fr. Hesburgh was in Rome (a practice he had stopped in 1969).

As for John Paul II, Fr. Miscamble

identifies four issues Fr. Hesburgh had with him, including a perceived threat

to academic freedom (which, by his telling in 1998, he saw occur three years

after his resignation in the 1990 Ex

Corde Ecclesiae). In the nine years between John Paul’s election in 1978

and Fr. Hesburgh’s retirement in 1987, and in the years after 1987, Fr.

Hesburgh never tried to establish a personal relationship with the Pope. Yet,

they had so much in common: They were born three years apart. Both had received

doctorates, both had an abiding concern with the promotion of the laity (the

subject of Fr. Hesburgh’s dissertation), both had attended Vatican II and

supported it, both had traveled (the pope’s travels included the U.S. for the

bicentennial in 1976 when the then Cardinal held a conversation at my then

parish, Annunciation of Washington DC), both were multilingual, both had taught

at university (the pope for over 30 years), both were opposed to Vatican

bureaucracy (the pope was the first non-Italian in hundreds of years).

Fr.

Hesburgh’s sour relationships with Paul VI and John Paul II are telling

indications of his estrangement from the Church that prevented him from making

Notre Dame a great, even the great, Catholic university. His current successor,

Fr. John Jenkins, continues this legacy of estrangement.

Heh. Thunder's sister is a member of our parish here in SE Wisconsin...and his brother-in-law is a mildly Left-ish fellow. The Catholic world is small, indeed!!

ReplyDelete